What Chairs Can Teach Us About the Safety Net

May 25, 2019

This is an adaption of a talk I gave at the CfA Summit Conference in 2019 to an audience of service designers, civic technologists, and government workers.

This is an adaption of a talk I gave at the CfA Summit Conference in 2019 to an audience of service designers, civic technologists, and government workers.

I design for the safety net. Like many of you, my goal is improve public services. At Code for America, I design services that help people access food stamps, medicaid, and tax credits. Unlike designing something like a car or poster, sometimes I find it kind of difficult to wrap my head around what it is exactly we are designing. Today, I want to share a story that helped me develop a good perspective on what we all do.

The story I want to share is about a chair. For industrial designers, chairs have always been the object to design. While other objects might be crafted with clean lines and mathematical proportions, a chair eludes the obvious because it needs to conform to the human body.

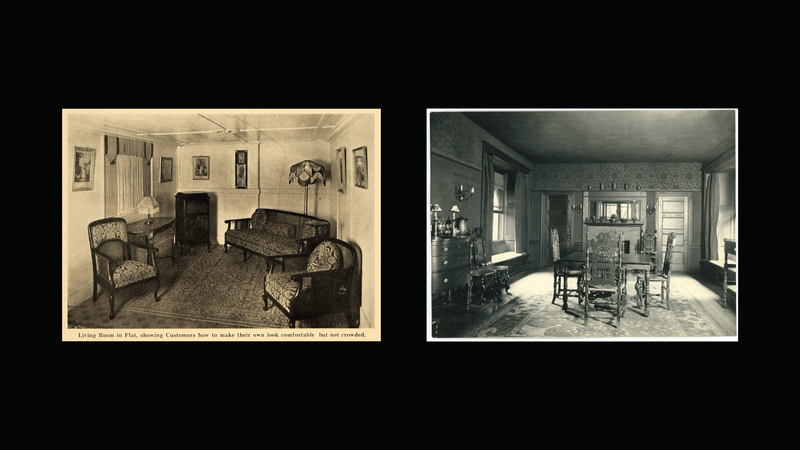

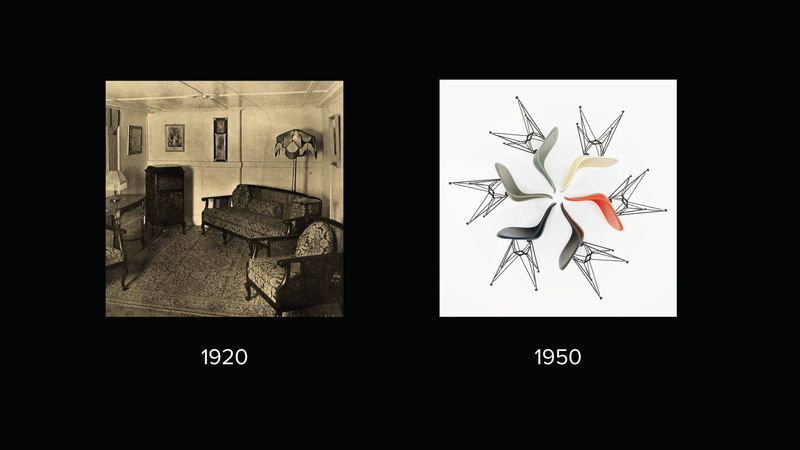

This is what a chair looked like in the 1920’s: different pieces of wood assembled to provide a seat, a backrest, and structural integrity. Expensive chairs might be upholstered to make them more comfortable.

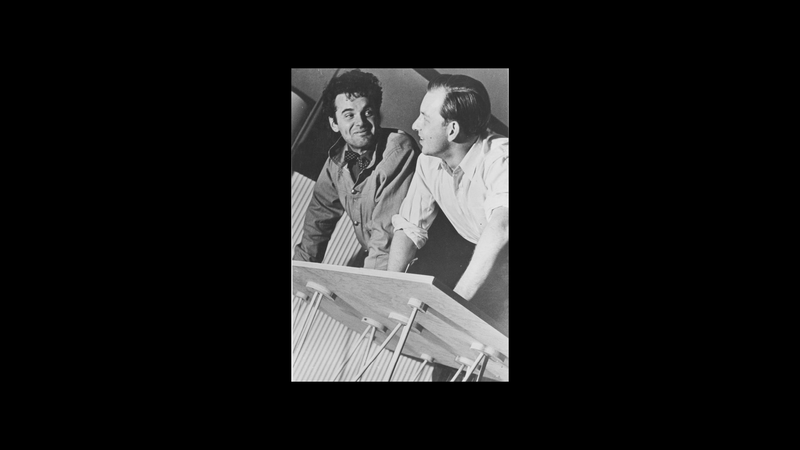

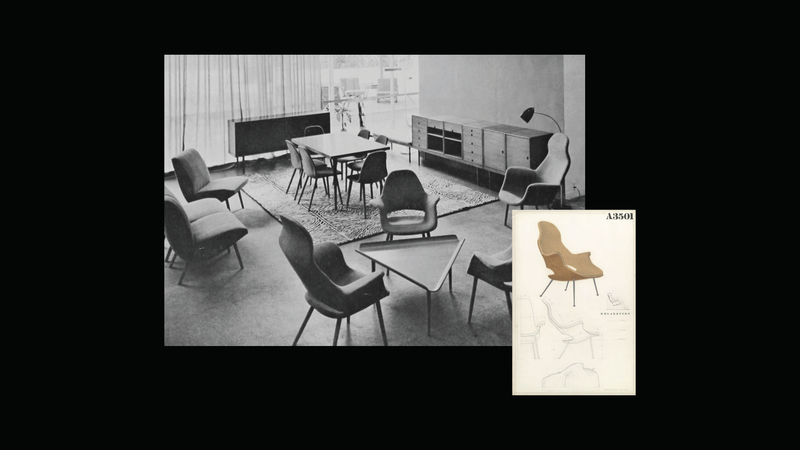

In the 1930’s, a group of young unknown designers had an idea for a better chair. They imagined a sturdy singular form shaped to fit the human body. By doing this, they hoped to create something comfortable without the need of a cushion. Perhaps equally as important, by simplifying the construction of a chair, they sought to make something great and affordable for everyone. Or in their words:

Make the best for the most for the least.

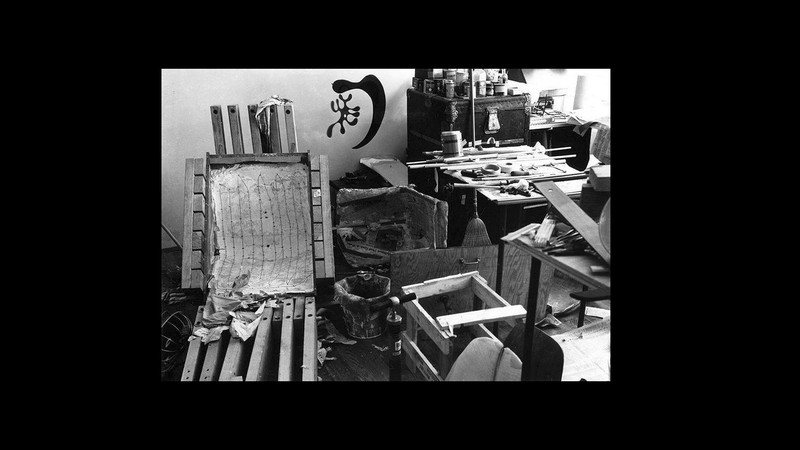

At the time, this group of young designers had found an interesting new technique of working with wood. By steaming thin sheets of plywood and pressing them together with molds, they could create a wide variety of different organic forms. They tried and tried but couldn’t quite achieve what they wanted without the wood splitting. It was a fight against the material they worked with.

The final design had to be upholstered anyway in order to conceal the cracked wood. It wasn’t a bad chair but it didn’t live up to the expectations they had. Here, they learned an important lesson.

Bringing ideas to life requires a craftsmanship of the material at hand.

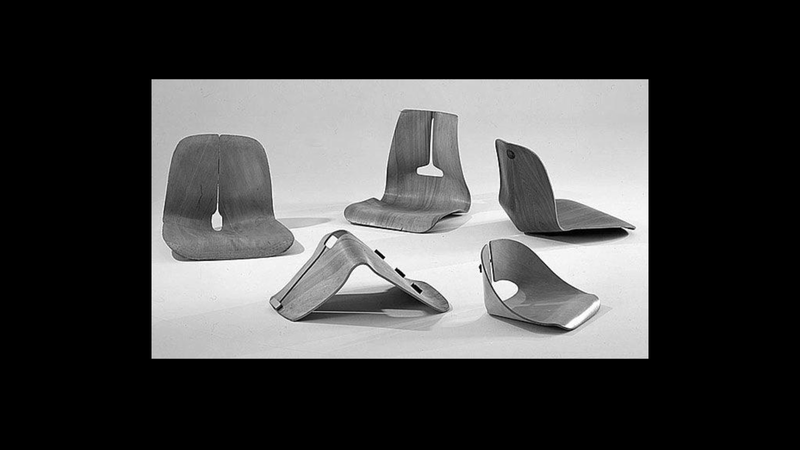

While these designers hoped to continue making furniture, the times demanded other priorities. The year was 1941, America entered the Second World War and this group of designers received their first large commission: making leg splints for wounded soldiers. They saw an opportunity here to perform their civic duty and also to perfect their craft of molding plywood. They learned by placing strategic cut-outs in the wood, you could reduce the strain placed on the wood, enabling a wider variety of shapes. Over the course of a few years, they were able to manufacture hundreds of thousands of splints. When the war ended, they went back to the drawing board and sought to design a chair with their newfound experience. The learnings from the original chair helped them to design an innovative leg splint. In turn, the learnings from the leg splint helped them to design a better chair. This was another important lesson for them.

Inspiration comes from making the unlikely connections.

While this second chair was a great iteration, it still felt short of the original vision. It was still not a singular form and it was expensive to manufacture. Today, you’d perhaps find this chair in the home of design historian or a high-end office but it was not “the best for the most for the least.”

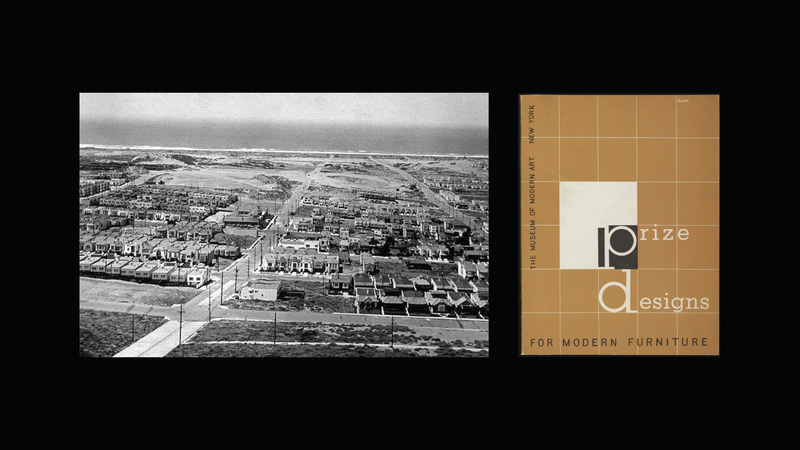

With the war behind them, designers were given another calling: creating affordable furniture for veterans and new families. It seemed like the perfect opportunity for this group of designers to put their mantra to the test.

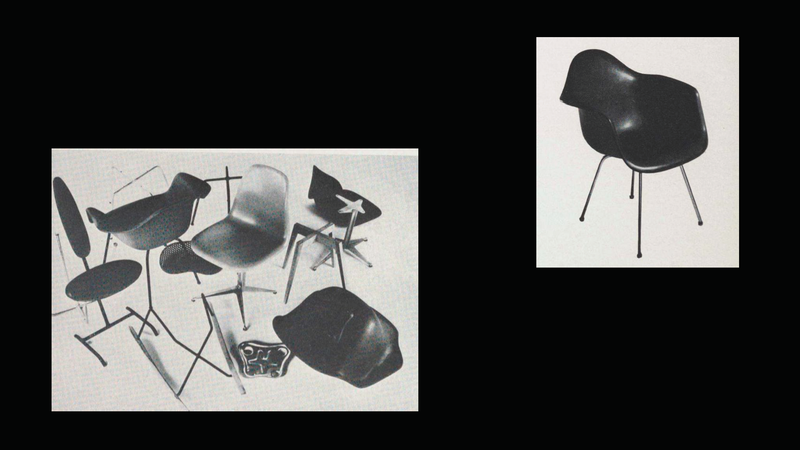

To make it cheaper and achieve the singular form they wanted, they realized they had to move away from molded plywood as much as they loved it. They spent years trying various new materials before landing on fiberglass. Once they did, they still had to design a entirely new manufacturing process for it.

To pick the perfect colors, they studied what best matched the interiors of most peoples’ homes.

They designed a modular set of different bases and seats to be used in a variety of circumstances.

They sweat the details that no one else cares about.

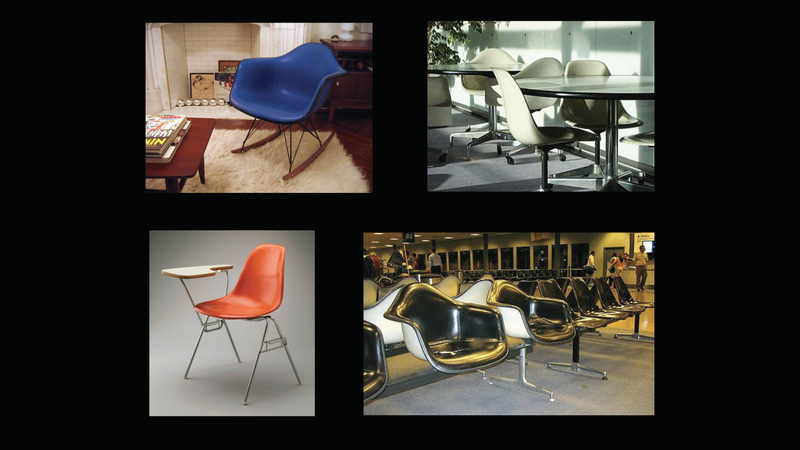

In 1951, they released their fiberglass shell chair to the world for $20 a pop. By doing the hard work of making something simple, they were finally able to make the best for the most for the least. Today, the shell chair is ubiquitous. It’s everywhere from homes to schools to offices to airports.

But given the historical perspective, it isn’t hard to see that this chair was a compelling evolution over what existed two decades earlier.

As some of you might have figured out, the designers were none other than Ray and Charles Eames. As a wife and husband team, they oversaw a group of talented designers. This chair marked the beginning of an incredibly creative and prolific studio. They ended up working on everything from furniture to buildings to toys to documentaries to museum exhibits. Learning about how they worked opened up my eyes to what a truly innovative design process looked like. Unfortunately, because of their fame, this chair isn’t quite so cheap anymore but it certainly was at the time.

So. What does this have to do with the work we all do?

What the safety net looks like today.

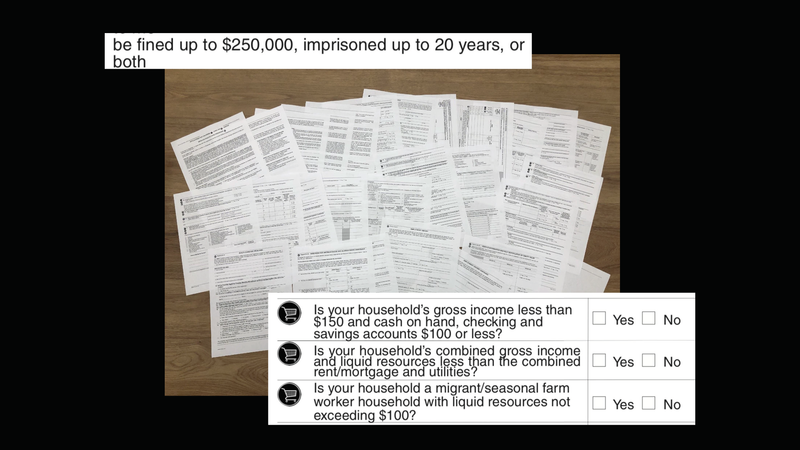

For tens of millions of people every day, here’s what accessing the safety net looks like in 2019.

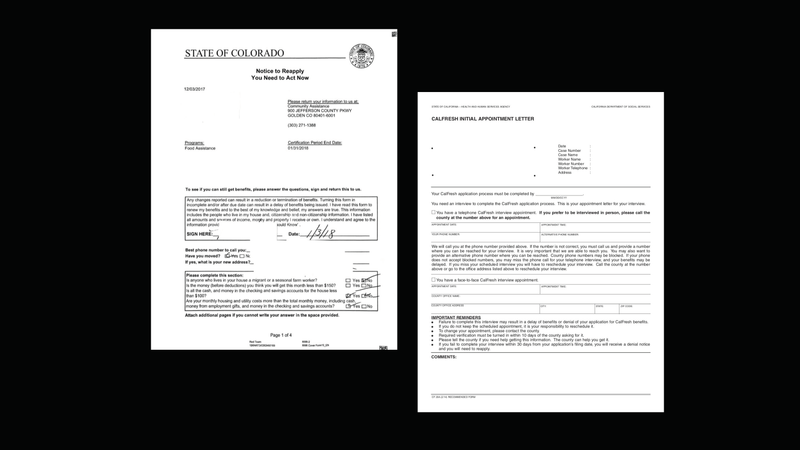

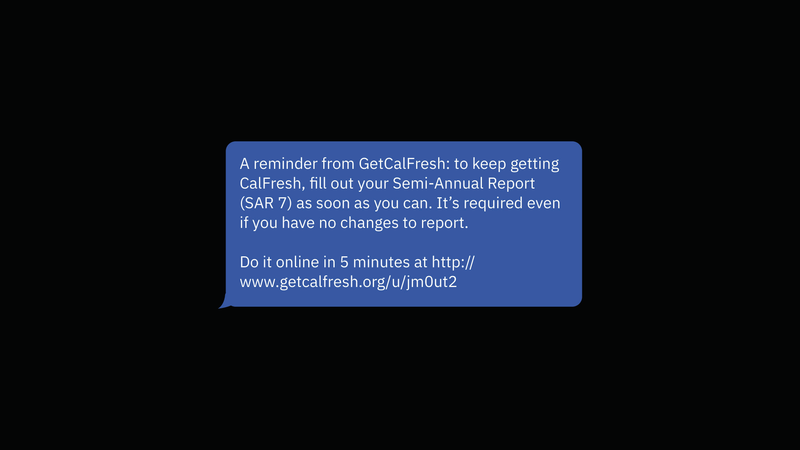

Here’s how we communicate with applicants. We rely on physical mail that takes days to arrive and is easily misplaced. We call clients unannounced from numbers they don’t recognize. Many times, we don’t leave a voice message or provide them a way to call back. How many of you pick up calls from numbers you don’t recognize?

Here are the lobbies that people wait in. To be fair, some lobbies are clean and modern. I’ve even seen some with free child care. But others are surrounded by gaurds, make you go through airport-level security, just to have you wait for hours.

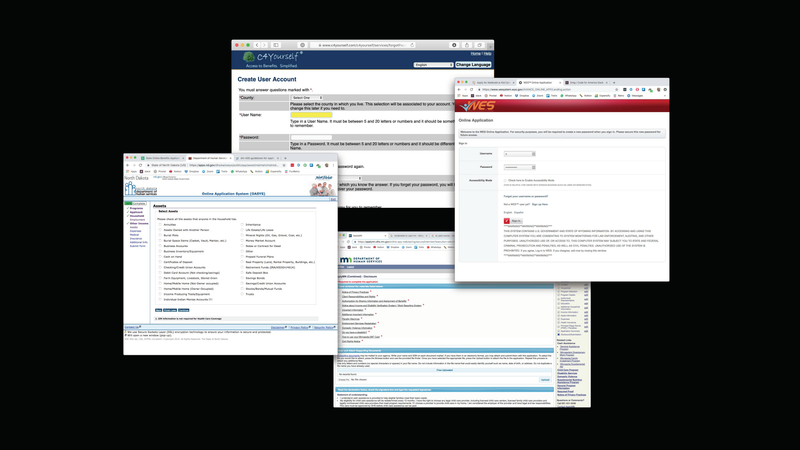

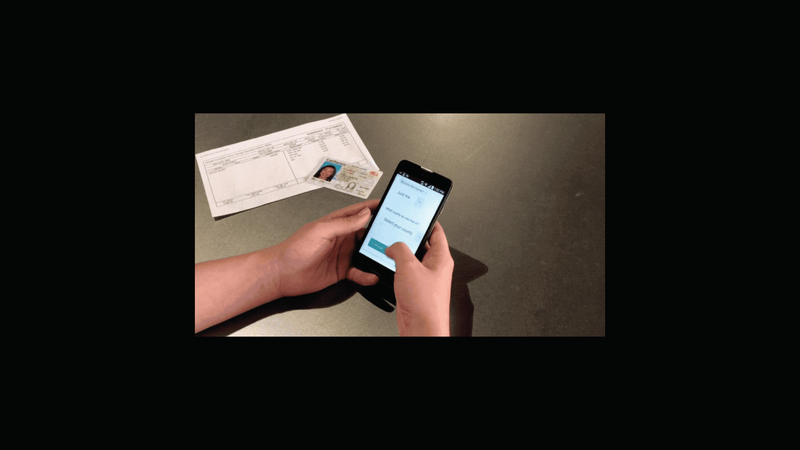

We spend hundreds of millions building complex websites that do not work on the devices that people have at hand - smartphones. Often, the front lines workers on end up fulfilling the role of a cushion to a very unpleasant chair. They worked tirelessly and patiently but inevitably, we end up seeing a high rate of burnout. Today, the safety net does not conform to the shape of the people it’s designed to serve. It is not made to be the best for the most for the least.

What might the safety net look like in 2030?

What I hope is that in ten years, what this country views as the safety net is dramatically different from what it looks like now. It won’t come easy though. Like the shell chair, a better safety net must start with a vision for something better.

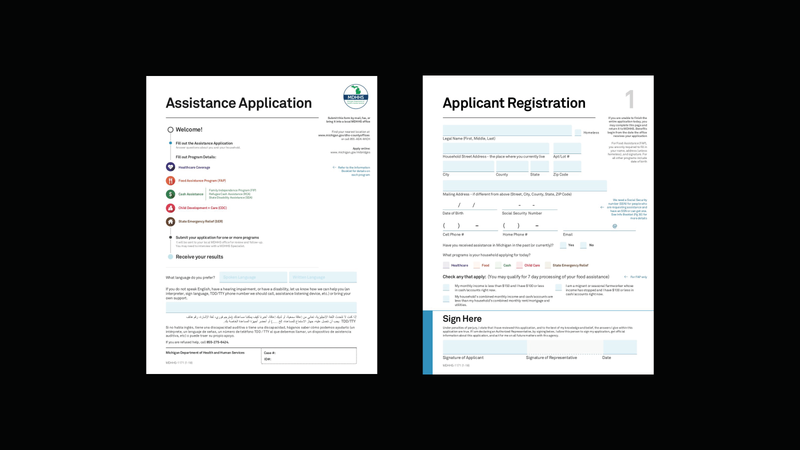

A better safety requires us to better shape the materials we already use. This means designing better forms, phone systems, lobbies, and policy.

As new materials emerge through technology, we must also learn how to work with them too. We must understand the new opportunities they present and be cognizant of the limits of what they can offer. As Lou Downe said yesterday, technology can show us what we can do. Design will show us what we should do.

A better safety net must accommodate the complex realities of society. We must do the hard work of making it simple. A better safety net will take inspiration from unlikely sources. It will require sweating the details no one else will care about. It will require a deep collaboration not just between designers but with all of us: policy-makers, social workers, engineers, advocates, and the public.

If we do our job right, the safety net of the future will feel very different from the safety net we have today. It won’t feel innovative to the people using it but hopefully it also won’t feel painful. It will feel like we made the best for the most for the least. It will feel like sitting down on a plain and comfortable chair.